KEY POINTS

- OSP has failed to curb corruption in Ghana, says Sam Okudzeto.

- Duplication with Attorney-General’s office reduces efficiency and accountability.

- OSP’s mandate may be better served by strengthening existing prosecutorial institutions.

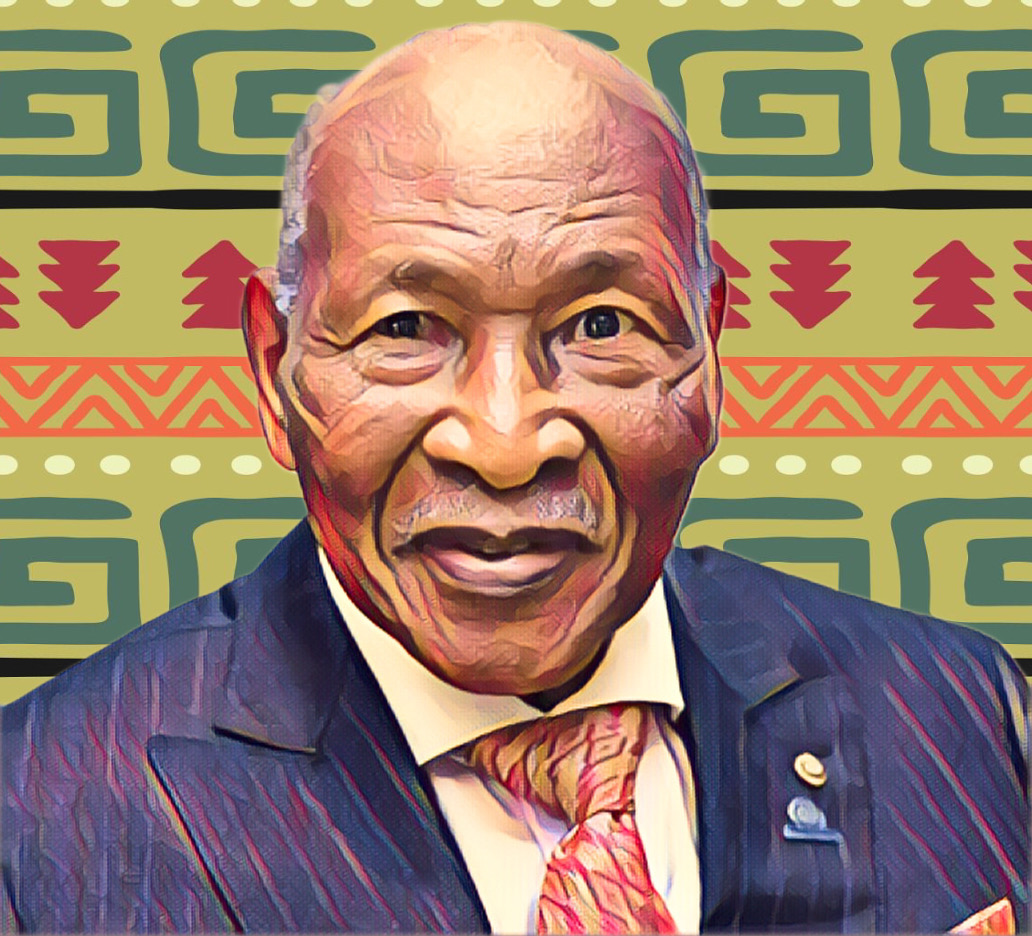

Former Ghana Bar Association president Sam Okudzeto has delivered a blunt verdict on the Office of the Special Prosecutor (OSP): it has failed to achieve its purpose.

Speaking on December 8, he said corruption remains visible and pervasive, with the institution making little impact. “Everywhere you turn in every institution, you see it openly. People are no longer even afraid,” Okudzeto said. “They demand money for services already paid for. That’s the reality we live in.”

Duplication hinders special prosecutor’s effectiveness

Okudzeto argued that the core problem is institutional duplication. The Attorney-General’s Department already holds authority to prosecute criminal offences, including corruption. He questioned why a separate institution was created for the same task.

“You have a Director of Public Prosecutions in the Attorney-General’s office. That role covers corruption,” he said. “Creating another institution for it is redundant. It doesn’t make corruption any different from other crimes.”

When pressed on whether the OSP should be scrapped, he agreed, noting that countries appoint special prosecutors only for specific, one-off issues. “You don’t build a whole institution around a single individual,” he said, warning that this approach is risky and undermines accountability.

Strengthening existing institutions could yield better results

Okudzeto aligned himself with critics who argue for dismantling the OSP and bolstering the Attorney-General’s office instead. He emphasized that building institutions around untested individuals is dangerous, and warned against the tendency to over-rely on a single appointment.

“The real solution is to empower those already trained and mandated to prosecute crimes,” he said. “It’s not about creating institutions around individuals. That’s risky, and it doesn’t work.”

His comments add fuel to ongoing debates in Ghana over the effectiveness of anti-corruption frameworks and whether specialized institutions deliver results, or merely duplicate existing powers with little oversight.